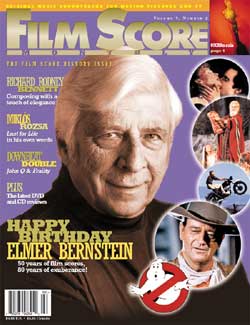

The Man With The Jazzy Sound

Elmer Bernstein's Cool Jazz, Part 1: The '50s

Mark Hasan | Film Score Monthly

How the composer created one unique score after another—yet maintained a personal style.

Following Alex North’s landmark 1951 score for A Streetcar Named Desire, a handful of composers made their mark by exploring the possibilities of writing traditional film music within the jazz idiom. Throughout the decade, worthy contributions were made by a number of up-and-coming composers, including Leonard Rosenman (Rebel Without a Cause) and Henry Mancini (Touch of Evil).

With the exception of Mancini, who inaugurated a new kind of easy-listening jazz in the ’60s (particularly with the Peter Gunn television scores and his later film work for director Blake Edwards), only Elmer Bernstein returned regularly to jazz music. Bernstein would write three hard-edged jazz scores before 1960: The Man With the Golden Arm (1955), Sweet Smell of Success (1957), and Staccato (1959); with each project, he would use jazz in unique, creative ways, while furthering his own distinctive style.

In order to examine the many Bernstein jazz recordings released on LP and CD at various times, it seems natural to start with The Man With the Golden Arm. Scored in 1955 for producer-director Otto Preminger, it’s hard to imagine the film today with any other type of music. During the ’30s and ’40s, the norm would have been to use jazz music only as source material, often playing from a record player or radio, or heard during an on-screen performance. The story of Frankie Machine, aspiring drummer and heroin addict, would have been treated no differently, except Otto Preminger clearly wanted to immerse the audience in the character’s world; because musicians live and breathe their music, the audience would have to do the same.

Drummer Shelly Manne and trumpet players Shorty Rogers and Pete Candoli were therefore allowed an unusual amount of space within select dramatic cues. Recalls Bernstein, “[Shorty] was a very cool guy, his ego was absolutely in the right place.”

Bernstein’s musical childhood was influenced by his father’s love of jazz and plenty of jazz records spinning on the turntable. In high school, Bernstein had a small band, and though he played a great deal of jazz music, he knew what a Shorty Rogers could contribute to his film score. “Once I got the themes going where I wanted to go with it, I was somewhat dependent on Shorty; Shorty did not do all of the arrangements, but he did a couple of them.”

Memories of Shelly Manne are equally joyous: “Shelly was one of my favorite people in the whole world. He had a great sense of humor, and he was always fun to be around. As a drummer he was very inventive. Let me put it this way: Generally, I tend to be rhythmically very active, and Shelly got a big kick out of that.”

Not surprisingly, Golden Arm begins with Shelly Manne’s drum riff, followed by a chorus of belligerent brass, all quickly overtaken by the trumpets. Once Frankie’s cocky blues theme is heard several times, the entire orchestra joins in, creating a nasty whirlwind—a sensation that foreshadows Frankie’s abusive fall into drug hell. As organized chaos comes to a pause, a trumpet solo guides us through the city streets as we’re introduced to Frankie: energetic, optimistic and sober.

The original Decca record ran 45 minutes—unusually long among soundtrack albums—and contained a large body of score and source cues. Though the album master was imperfect from the start (the old LP featured distortion in the high end), the importance of the recording can’t be underestimated.

Many of the score selections are tightly edited together; not a good thing since the edits are imperfect, and the album’s first cue, “Clark Street,” jumps from the opening titles to the street section, then hastily to juke box/big-band source.

The score’s secondary theme, “Zosh” is characteristic Bernstein—high strings playing a sensitive melody, while the bass and celli play ascending/descending chords in the background. The layered strings eventually come to a delicate pause, and a carefully chosen instrument—oboe, clarinet, sax, or, particularly, piano—takes over, often adding to the scene’s delicate mood. While the strings give us the ambient emotions, the solo instrument conveys each character’s emotional fixations; this ploy is one of several familiar patterns in Bernstein’s calculated approach to scoring drama. “Zosh” ends with a short piano phrase—an incomplete bass line—which appears as a warning to us: Frankie’s going to fall big time, very soon.

Heard so forcefully over the opening titles, the familiar thematic bars appear in “Frankie Machine,” only this time Shorty Rogers gives us a soulful, lengthy solo, fluttering over the band, while Manne taps an exotic rhythm, chasing Rogers until he finally gives up, finally letting the mad drummer show his stuff.

The repetition of Frankie’s theme is important, particularly during the bold scene where Frankie shoots up and begins his path to sweaty euphoria. This time, however, Bernstein holds back on the brass, using the strings at a lower volume and creating a marvelous swirling effect. Once the poisoned pleasure hits Frankie’s nervous system, the brass reappear, sadistically mocking him.

Frankie’s heroin high is punctuated by a sustained note on a rough-sounding organ, creating a strange and surreal effect. Rumbling percussion suggests Frankie’s inner torment, undulating constantly, until the main theme returns to close the cue as horns blare furiously.

The film’s second and equally important theme is “Molly,” composed for the woman who helps Frankie to the road of recovery. A delicate theme played by piano and flutes, it’s another classic Bernstein composition, full of pity and affection, two qualities Frankie is unable to find for himself.

Some film composers are adept at writing only themes and songs, and require brilliant orchestrators to develop their material. Composers like Bernstein rise above these limited tunesmiths because they are blessed with a deeper understanding of musical construction. Having heard “Molly” in its most innocent form, one can hear how “Breakup” takes the tender theme and turns it on its end. Starting with a frenzied rhythm on piano, bass and drums, Molly’s theme reappears in a more desperate assemblage: As the strings and woodwinds drag out the melody, the percussion seems to beat it away, making room for Frankie’s theme as he falls off the wagon again.

Bernstein’s skillful writing deconstructs Frankie’s theme in “Desperation” as Frankie searches for another hit. As oboe, flutes and clarinet play sustained, warm notes, the strings move from highs to brooding lows, followed by a sarcastic sax. The basic rhythm quickly appears—desperate, driven, harsh—only to culminate in an explosion of drum riffs. Frankie’s hunger is then mocked by a hideous honky-tonk piano, and the cue drifts away with the theme’s bass line.

A final cue worth mentioning is “Audition.” Though primarily a source cue, it reveals Bernstein’s grasp of big-band arranging, and in later years he would revisit the genre in television and film, particularly in The Silencers (1966).

The Man With the Golden Arm would prove to be immensely beneficial for all connected with the score. Armed with a powerful calling card and a best-selling album, Bernstein’s career was set. The Decca LP would be reissued several times over the next 30 years, eventually making it to CD in Japan in 1992, and has just been reissued as a Polygram import.

Both Shorty Rogers and Shelly Manne would continue their own busy careers, though in addition to session work on film scores, they would individually score television shows and the occasional feature.

While Golden Arm was making the hit parade, Decca approached Bernstein and proposed a non-film album—and an unofficial sequel—using big-name musicians performing similar, big-band instrumentals. Titled Blues and Brass (currently unavailable on CD), the 1956 album featured a collection of 12 original Bernstein tracks that act as an interesting stylistic bridge between Golden Arm and Sweet Smell of Success, made the following year.

Using a familiar introductory piano phrase, performed with manic energy, “Return of the Man” clearly recalls Golden Arm’s “Breakup: Flight” cue. “Blues at Five,” on the other hand, evokes a cold, nighttime walk down a bleak, empty street. Similar to Sweet Smell’s angry style, a series of gradual brass build-ups is repeatedly ripped apart by a circular piano phrase, which maintains an even tempo and heightened level of tension.

A variety of mood pieces add emotional balance to the album, including “The Poor People of Brazil,” a light, fluffy and easy-going piece of exotica. “Central Park—4 AM” is a classic Bernstein meditation, primarily consisting of solo trumpet backed by small orchestra. Smooth and breezy, Bernstein’s brief sax and guitar passages wistfully allude to some of the more eccentric characters in the composer’s evocation of Central Park.

With Shelly Manne active throughout the album, percussion reigns supreme in “Wild and Crazy,” a furtive variation of “Return of the Man” that builds with maddening tension as the brass section and percussion slug it out before a calming resolution. In “Smooth,” a young Andre Previn deftly performs a lively, albeit short solo, briefly dipping into classical patterns. The year 1956 would prove to be an important one for Previn and Manne too, as the two stellar musicians would collaborate on a series of classic albums derived from stage plays, including My Fair Lady and West Side Story, for Contemporary Records.

Sweet Sleaze

Bernstein’s next Decca soundtrack was Sweet Smell of Success, scored in 1957. Produced by Burt Lancaster’s partnership—Hecht, Hill and Lancaster—the film followed Sidney Falco (Tony Curtis), a sleazy press agent hired by New York’s powerful columnist J.J. Hunsecker (Lancaster) to find dirt on his sister’s fiancé to prevent their union.

Bold and brash describe Bernstein’s powerful score, immediately evoking a sense of sleaze, devious back-stabbing and the omnipresent coldness of the city. Beginning with breezy drums and burlesque trumpet, “The Street”—the film’s main title—is formalized as a brutal group of brass, piano and percussion hammer out the film’s main theme. A brief respite comes from a more subtle group of trumpets, playing the main theme with restrained percussion, only to be forced back to the angry orchestra to conclude the title track.

“Hot Dogs and Juice” introduces the film’s secondary theme, also known as “Goodbye Baby.” Arranged throughout the score by Bernstein, the theme is credited to Chico Hamilton and Fred Katz, founding members of the Chico Hamilton Quintet, who also appear in the film. Drummer Hamilton and cellist Katz were revolutionary in the late ’50s for combining classical composition with jazz, resulting in many avant-garde works; their writing was unique, and though still clearly jazz music, it lends itself well to the film medium.

Much of the score is based upon these two themes, and while effective in the film, their placement on the Decca soundtrack album does, sadly, become repetitive in spots, often allowing three variations of Bernstein’s theme to follow in a row. That said, the variations are sublime, often appearing as juke box, big band, small combo and straight underscore.

The more dramatic, functional cues reflect Falco becoming caught up in Hunsecker’s lying, cheating world, where deviousness is the means to achieving a byline. Indecision, inner torment and humiliation are often conveyed through Bernstein’s strings: high registers express extreme passion and tenderness, while the lower strings allude to a darker force constantly pulling away at Falco’s increasing guilt.

Much like the records for Johnny Mandel’s I Want to Live! score, two albums were released by Decca. Both mono recordings are quite rare nowadays. The second album, featuring the jazz combos, is worth mentioning, because it acts as an extension of the film score. The record has sizable source cues, and the second side contains a 16-minute suite, Concerto of Jazz Themes, which summarizes the film in the recognizable, moody style of Chico Hamilton’s quintet, with Fred Katz’s cello adding extra drama.

Both Katz and Hamilton would write a few film scores on their own: Katz’s brief film period would include scores for Roger Corman’s Little Shop of Horrors, A Bucket of Blood and Ski Troupe Attack!—exploitation fare blessed with remarkably well-crafted music. Hamilton would later score Roman Polanski’s first English-language film, Repulsion (1965), and score a handful of later films, including Mr. Ricco (1975), starring Dean Martin.

Television offered many composers a chance at a little financial stability, though Bernstein seemed busy enough not to have to worry too much about dry periods. Amid the straight dramas, biblical epics and war films, Bernstein also found time to produce three more non-film jazz albums before the decade was up.

Themes and Variations

Considering the meteoric success of rock ‘n’ roll in the ’50s, it’s interesting to observe how a number of film composers produced light, film-theme collections during this time—essentially recordings aimed at the dinner party crowd. For RCA, Alex North released North of Hollywood, while Dimitri Tiomkin’s Movie Themes From Hollywood appeared on Coral Records. Alfred Newman produced Themes! for Capitol, and Victor Young issued numerous orchestral albums for Decca.

After the success of The Ten Commandments albums, Elmer Bernstein produced two film theme collections for Dot Records in 1958: Love Scenes and Backgrounds for Brando.

Though Newman’s Themes! album is incredibly schmaltzy, Bernstein’s recordings have stood the test of time, with tasteful arrangements for a number of commercial favorites: Gone With the Wind, Lili, Raintree County and Around the World in 80 Days. Only The View From Pompey’s Head is a Bernstein original.

Selections from films like Sayonara, though clearly composed by Franz Waxman, are distinctive Bernstein arrangements, with characteristic pauses, and piano solos reflecting the composer’s sensibilities. Even purists would agree the various selections from different composers are treated with extra care, and that may be an indication of how the young Bernstein was in awe of his peers. These two LPs are important footnotes because, years later, the composer would revisit some of these veterans, re-recording some of their neglected works in the ’70s in 13 of the 14 volumes that make up Elmer Bernstein’s Film Music Collection.

Released in a fairly effective fake stereo format, selections from both Dot albums were later reissued on one LP in straight mono by Hamilton, a Dot subsidiary; Backgrounds for Brando was also reissued in England by Contour Records as Theme Music From the Great Brando Films. Sadly, both LPs remain unreleased on compact disc.

Unlike Henry Mancini, whose first feature score, Touch of Evil, led to work in television, Bernstein had already composed music for several high-profile dramas and epics before his television period. Once Mancini’s jazz music from Peter Gunn topped the music charts in 1958, it seemed natural for television producers to approach Bernstein.

Of his time with the small screen, Bernstein’s best work is found in Staccato, starring John Cassavetes as private detective and jazz pianist Johnny Staccato. Originally released by Capitol Records and reissued on vinyl by England’s That’s Entertainment Records in 1982, the Staccato album remains an outstanding work of stereo recording and engineering techniques that begs a digitally unadulterated CD release.

Like Mancini, Bernstein wrote the show’s theme music, underscore, and source cues, using orchestra and small jazz combos. Staccato is also Bernstein’s third great jazz score of the ’50s. Though lighter in tone than Sweet Smell and Golden Arm, Staccato retains a potent edge. It’s hard not to compare Peter Gunn with Staccato, since both series spawned successful albums. A major difference, however, was Mancini’s decision to tone down his music.

Smooth and upbeat, Peter Gunn began a trend of easy-listening jazz—mood music to play during a dinner party (or first date). Gunn’s popular themes were also re-recorded many times in the following years, with only drummer Shelly Manne and trumpet player Joe Wilder offering harder interpretations on their own collections, for Contemporary and Columbia Records, respectively. The best-known re-recordings of the Staccato theme are by Buddy Morrow (recorded for RCA’s Double Impact, and recently reissued by RCA Spain) and Mundell Lowe (on RCA Camden’s More TV Action Jazz, currently unavailable on CD).

Bernstein, however, would later take advantage of Staccato’s popularity in a subsequent compilation release, but for the original soundtrack album, he chose to record light jazz combos with vibes, electric guitar and lively percussion (such as “The Jazz at Waldo’s”), and some straightforward underscore (“Deadly Game”).

Perhaps Bernstein felt the inclusion of a few dramatic cues would separate his work from the countless television soundtracks that started to appear in record stores. Even Nelson Riddle, master of suave orchestrations, radically toned down his Untouchables material for the 1960 Capitol LP. Had Bernstein been more commercial-minded, marvelous, driven cues like “Greenwich Village Rumble” and “Pursuit” would have remained in the producer’s closet. Besides, Capitol Records provided the composer with a better opportunity to be “nice and light” in his next unusual release.

Paris Swings (currently unavailable on CD), starring “Elmer Bernstein and the Swinging Bon Vivants,” was a lofty concept album, featuring popular standards and a few film themes (providing they had some connection to things French).

“Now that was a dumb idea,” recalls an amused Bernstein. “That was a really dumb idea, but boy, talk about hot people on an album.” In addition to regular all-stars like Shelly Manne and bassist Red Mitchell, a young, “real hot pianist” named Andre Previn also performed on several tracks.

Why produce Paris Swings? Perhaps the idea stemmed from Michel Legrand’s classic 1954 album, I Love Paris. Columbia Records had achieved much success with Legrand’s own French, Spanish, and Brazilian-themed collections of esoteric standards, and Capitol may have toyed with their own series of dinner music exotica. While Legrand focused on drippy orchestral presentations, however, Bernstein’s album was better grounded, via small jazz combos.

Bernstein arranged two-and-a-half- and three-minute versions of “Autumn Leaves,” “Paris in Spring,” “La Vie en Rose,” and the irresistible “I Love Paris.” The short album also contains two Bernstein originals: “Adieux d’Amour” and “Souvenir du Printemps.” The latter, however, is a Spanish-flavored ditty that features some nice piano work, perky trumpets and marimba. The cue is also of note because it appears to be an early draft of “Teresina,” a composition later used in Walk on the Wild Side (1962). From 1955 to 1959, Elmer Bernstein released three classic jazz soundtracks and four collections of favorite film and non-film music. Quite a feat, considering he had scored upward of 30 films, 12 TV series, three documentaries, nine short films, a concert work, and a play, by 1960.

Though the composer would write his best-known works in the next decade—The Magnificent Seven, To Kill a Mockingbird and The Great Escape—he would continue to return to the world of jazz when the opportunity and project were just right. And though the pop realm would inevitably affect the style of later film scores, it seemed that, for another decade at least, Bernstein would find great joy by combining the best of both worlds.

NEXT TIME: In Part 2, we’ll look at the Bernstein’s WALK ON THE WILD SIDE and THE SILENCERS, his Ava compilation LP, which featured themes from THE RAT RACE, and other film and TV productions. —FSM

Reprint Courtesy of Film Score Monthly