Hollywood’s Score Keeper

Elmer Bernstein is the composer behind many classic movie themes. A tribute and screenings survey his 50 years of work.

Jon Burlingame, Special to The Times

Photo by Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times

Many people spend a lifetime toiling at the same job. What’s unique about Elmer Bernstein—now celebrating his 50th year as a composer for films—is that few in this very select group manage to survive so long in such an exacting, often frustratingly trendy profession.

“Elmer Bernstein is movie music,” says film historian and commentator Leonard Maltin. “He has spanned the waning days of the studio system and the golden age of Hollywood to the 21st century, with his talents and skills intact. He has done as much to promote appreciation and understanding of film music as he has pursuing his own career.”

The numbers are impressive enough: more than 150 film scores and an estimated 80 for television, not to mention an Academy Award and another 12 nominations in all three Oscar music categories (original score, song, adaptation score). But Bernstein’s lasting achievement may be his creation of a handful of truly classic movie themes:

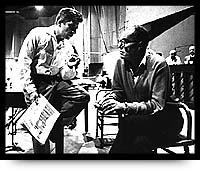

Frank Sinatra was on hand when Bernstein, right, conducted the score for the star’s 1958 “Kings Go Forth.”

The driving jazz for Frank Sinatra’s heroin-addicted drummer in “The Man With the Golden Arm” (1955).

The alternately majestic and reverent music of Cecil B. DeMille’s “The Ten Commandments” (1956).

The rousing western anthem of “The Magnificent Seven” (1960), which became even more famous (some might say infamous) as the theme for the cowboys of Marlboro Country before cigarette ads were banned from the airwaves.

The lyrical, quietly moving music of “To Kill a Mockingbird” (1962), now hailed as a landmark in movie scoring.

The slinky, other-side-of-the-tracks jazz for the New Orleans brothel tale “Walk on the Wild Side” (1962).

The jaunty, thumb-nosing march for the prisoners of war plotting a massive breakout from a German camp in “The Great Escape” (1963).

Some, if not all, of those tunes are familiar to most Americans, even if they haven’t seen the movies. Film buffs might recognize even more, from the lush music of “Hawaii” (1966) to the offbeat noir score of “The Grifters” (1990), the so-serious-it’s-funny music of “National Lampoon’s Animal House” (1978) and a pair of television themes: the “National Geographic” fanfare and the evocative melody of “Hollywood and the Stars.”

“It doesn’t feel like 50 years,” says Bernstein, who acknowledges that his versatility has been a big factor in his longevity. “I think I have demonstrated an enthusiasm for change, and that’s fairly infectious. I would hope that some of the energy and joy that exists in some of the work would communicate years and years from now.”

Tonight, Bernstein will be honored for his lifetime of work at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in Beverly Hills. The tribute will include appearances by directors John Landis (“Animal House”) and Carl Franklin (“Devil in a Blue Dress”), actor James Coburn (“The Magnificent Seven”), producer Noel Pearson (“My Left Foot”) and jazz composer Terence Blanchard.

On Friday, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art begins a four-weekend series of Bernstein’s films, including, on Nov. 16, the rarely screened “Summer and Smoke” (1961) in a dye-transfer Technicolor print, and, on Dec. 1, a new 35-millimeter print of the original roadshow version of Bernstein’s Oscar-winning “Thoroughly Modern Millie” (1967). On Saturday at 7:30 p.m he will be interviewed by fellow composer Cynthia Millar before a screening of his Oscar-nominated “The Age of Innocence” (1993).

But for the 79-year-old composer, it’s business as usual. He is in the midst of composing the score for Martin Scorsese’s epic “Gangs of New York,” now slated for a Miramax release next year (it had been scheduled for a holiday release this year but has been delayed). For Scorsese, Bernstein’s connection to Old Hollywood is one key to their ongoing collaboration. “He is certainly one of the great cinema composers of all time,” the director says by phone from New York. “The width and breadth of the work, the amount of work, shows a range that is quite unique. He isn’t noted for just one thing, you see. It’s an honor to work with him, because I admire not only his artistry, but his history and his knowledge. If I mention some film made in the 1930s or ’40s, he knows the film, he knew the people, how they worked and what they did.”

Bernstein is revered by many of the town’s younger composers. James Newton Howard (“The Sixth Sense,” “Dinosaur”) considers Bernstein among the most influential of composers. “Effortless is one of the words that comes to mind when I consider Elmer’s work,” he says. “With his scores, one never has the feeling that the music is working too hard. Somehow, he has always been able to achieve gigantic effect with the most gentle and graceful gestures.”

No Hollywood career of any longevity is without its peaks and valleys, however, and Bernstein’s has had plenty of both. Born in New York of Ukrainian immigrant parents, he was originally destined for a career in classical music. As a young pianist, he gave his first concert at age 15 in New York’s Steinway Hall. Encouraged by Aaron Copland, he undertook composition studies with several important teachers, including Roger Sessions and Stefan Wolpe.

World War II intervened, and the young composer got his first taste of writing music for drama by working on radio shows in the Army Air Force. After the war, he returned to the highbrow world of classical piano, but continued to dabble in radio scoring for the United Nations and producers such as Norman Corwin.

His break came in 1950 when writer Millard Lampell, an old service buddy, persuaded producer Sidney Buchman to hire the novice composer on a football movie he had written called “Saturday’s Hero.” It was scored at Columbia, which released the film in 1951.

“The atmosphere in those days was so different. It’s very hard for anybody to even imagine today,” says Bernstein, during a rare respite from work in his Santa Monica studio. “First of all, you had full support. You had an orchestrator, copyists, an orchestra literally at your disposal. The head of the department was himself a fine musician—at Columbia, Morris Stoloff—to whom you were basically responsible. Not the director. Nobody else.”

The next year, Bernstein’s music for the Joan Crawford thriller “Sudden Fear” attracted critical attention, but by 1953 he was virtually unemployable, reduced to doing pictures like “Robot Monster” and “Cat Women of the Moon.” Bernstein soon learned that he had been “graylisted” for his involvement with left-wing causes, and although he had not been a member of the Communist Party, he had written music reviews for the Daily Worker in the late ’40s. He wound up working as a rehearsal pianist for the ballet sequences in the film version of “Oklahoma!” and working with Danny Kaye’s wife, Sylvia Fine, jotting down her tunes for “The Court Jester” at Paramount.

A Paramount music executive took pity on Bernstein and introduced him to DeMille, who was then shooting “The Ten Commandments” and needed ancient-sounding music for dances. Bernstein recalls the legendary director’s first question to the then-32-year-old composer: “Do you think you could do for ancient Egyptian music what Puccini did for Japanese music in ‘Madame Butterfly’?”

Today, Bernstein thinks that if he had replied yes, he would have been fired. “I think I gave him the only answer that would have kept me there. I said, ‘I don’t know, but I’d like to try.'” Bernstein wrote all of the “source” music, the colorful songs and dances that were featured throughout the biblical epic. When Victor Young, who had originally been signed to write the dramatic music, dropped out because of ill health, DeMille assigned Bernstein to replace him.

“The Ten Commandments” and the groundbreaking jazz score for “The Man With the Golden Arm” catapulted Bernstein onto the A list of Hollywood composers. “Golden Arm” won him his first Oscar nomination and launched a series of jazz-oriented scores, including “Sweet Smell of Success” (1957), “The Rat Race” (1960), TV’s “Staccato”(1959) and “Walk on the Wild Side” (1962).

The jazz scores, plus the spate of westerns and dramas that would dominate the composer’s work throughout the ’60s, helped to solidify his reputation as a master of musical Americana. The robust, exciting music of “The Magnificent Seven” brought another Oscar nomination and offers to do westerns of all kinds, including seven John Wayne films, among them “The Comancheros” (1961), “True Grit” (1969) and “The Shootist” (1976).

“I really loved the westerns,” Bernstein says. “They were fun to do because they addressed themselves to a particular kind of Americana which started with Aaron [Copland]. Also, in my early years I spent a lot of time with American folk music. It was like discovering a magic world. I think a lot of that stuck with me; it was part of my musical heritage.”

Elmer Bernstein, left, with director John Sturges.

“To Kill a Mockingbird” remains a special memory. A recognized classic about racial prejudice in the small-town South of the ’30s, it won 1962 Oscars for Gregory Peck and screenwriter Horton Foote. Its understated music, much of it for chamber-sized ensembles instead of traditional full orchestra, has become a model for film composers ever since.

It wasn’t easily arrived at, however. “It took me weeks and weeks,” Bernstein confesses. “After the longest period of time, it came to me that what was going on here were a series of real-world adult problems seen through the eyes of children. That led me to the basic sound of the score: the piano being played one note at a time, something kids do all the time. Music-box-type sounds, bells, harps, single-note flutes were all things that suggested a child’s world.”

Even Peck remains in awe of the score. “The music that so moved us on first hearing, and haunts us today, is a work of the purest imagination,” he says. “It is the ultimate in film music: It fits and it is inspired.”

Bernstein’s career took a strange turn in the ’70s, thanks to a call from his son Peter’s old school chum, John Landis. Landis, then 27 and a film director, asked Bernstein to score his raucous college comedy “Animal House,” starring John Belushi.

“Elmer thought I was nuts,” Landis recalls. “I wanted the score to be essentially a straight one, and a dramatic one. When I showed him the movie and discussed what I wanted, he understood, and he did it brilliantly. There are comedic things in the score, but essentially he scored it as if it was a serious narrative.”

Almost overnight, Bernstein became the comedy composer in town. For the next decade, he was largely typecast in that role, doing “Airplane!” and many of the “Saturday Night Live” alumni movies, including Bill Murray in “Stripes” (1981), Dan Aykroyd and Murray in “Ghostbusters” (1984), and Steve Martin and Chevy Chase in “Three Amigos!” (1986).

The Aykroyd-Belushi “The Blues Brothers,” directed by Landis, is scored almost entirely with traditional rhythm and blues songs. “Except,” Landis says, “at one moment I needed God to touch John Belushi. And I thought, God music, hmmmm … Elmer Bernstein!”

Landis also talked Bernstein into adapting Mozart’s “The Marriage of Figaro” as the score for “Trading Places,” and Bernstein received a 1983 Oscar nomination for it. Music for smaller, well-crafted dramas like “My Left Foot” (1989) and “Rambling Rose” (1991), and the Scorsese films, shifted the balance once again for the composer.

Bernstein adapted Bernard Herrmann’s 1962 “Cape Fear” score for Scorsese’s 1991 remake, received an Oscar nomination for the elegant music of the director’s “The Age of Innocence” in 1993, and provided the musical atmosphere for his “Bringing Out the Dead” in 1999.

“[Elmer] is probably the first one to see the longest cut of the picture,” Scorsese says. “He’s the only one we trust to sit there and get a sense of what the movie is. Then we have long discussions about it. We talk about the characters and about the world they inhabit.”

[“Elmer Bernstein, above] is probably the first one to see the longest cut of the picture. He’s the only one we trust to sit there and get a sense of what the movie is. Then we have long discussions about it. We talk about the characters and about the world they inhabit.”—Martin Scorsese

In the case of “Gangs of New York,” a film about Irish immigrants arriving in 19th century New York City, Scorsese reports, “We’re going back to very ancient instruments of the period, and even before, to give a feeling of the primitive world that [the characters] are living in—the expression of their souls through the sound of those instruments, whether fifes or Irish or Scottish pipes, or certain kinds of drums that are used in the Celtic world.”

In person, Bernstein is both friendly and erudite, thoughtful and surprisingly optimistic for someone who has been knocking around show biz for more than 50 years. Actor Edward Norton, who hired Bernstein for his first film as a director (last year’s “Keeping the Faith”), says, “He is one of the most vibrant people I’ve worked with. It’s his very youthful enthusiasm that makes it so invigorating to work with him. He brings the full depth of his classical training and classic Hollywood experience to the table—but he brings with it the energy of a 28-year-old.”

It’s energy that Bernstein has applied, with varying degrees of success, in different arenas over the years. He has composed for Broadway and has two Tony nominations to show for it: 1968’s “How Now, Dow Jones” and 1983’s “Merlin.” He has an Emmy for “The Making of the President 1960” and penned such classic TV themes as “Riverboat,” “The Rookies” and “Ellery Queen.” And he has recently returned to his classical roots, having composed a guitar concerto for Christopher Parkening and now writing a string quartet as well.

The business has changed considerably during half a century, and not all those changes sit well with Bernstein. The emergence of the synthesizer, and the resulting reliance on keyboard improvisation instead of serious, beyond-what-your-fingers-can-play composition, for example. And “a tendency toward movies being more about things rather than people, about special effects. They’re not about interpersonal stories as much as they used to be, and that, of course, influences what you write.”

But Bernstein enjoys “being the magician, the person who can manipulate the emotions of the audience, unbeknownst to them.” He says he has no plans to retire (although he has homes in Santa Barbara, Woodstock, N.Y., and Warwick, England, and any one of them would be a suitable retirement spot).

Reflecting on his career, Bernstein says, “I can say that I can’t think of anything else that I’d have rather done with my life. I think I made a difference. It is an amazing human privilege to look back at your life and simply to be able to say that you had some part in making millions and millions of people feel better, two hours at a time.”

Copyright 2001 Los Angeles Times