Celestial Refrains

Cathy M.Winston | Lifestyles Magazine

“An interviewer once asked me to discuss my collaboration with Elmer Bernstein, and precisely why I chose to work with him. My first thought was: how could I not work with Elmer, when I had the chance? Simply put, he’s the best there is – the very best.”

Martin Scorsese, director

The maestro strides quickly out of the dressing room, his mane of white hair moving in concert with the gait, baton in hand, pale blue eyes focused, a man on a mission. He maneuvers through the phalanx of celli and violins and steps up to the podium. At once, the sight of a pair of bright red running shoes reveals his penchant for symmetry—they match the tiny teddy bear he has placed, boutonniere-style, in his suit pocket. He’s ready for action. And the young members of the Henry Mancini Institute Orchestra eagerly begin to play the unmistakable theme from “The Magnificent Seven.”

Elmer Bernstein knows the score.

This is a man who lives life to the fullest, traversing continents with the ease of a diplomat. Music is his passport, and his language. He moves from jazz to classical to modern to pop with equal aplomb. He keeps moving and renewing. Celebrating his 80th birthday in 2002, Bernstein is vital and restless, always looking to increase his knowledge, to adapt to the ever-changing musical terrain, to educate, and to learn. And fortuitous and fortunate it is for the multitudes who have listened to the music he’s composed.

Last year, the veteran film composer celebrated his golden anniversary of scoring films, the singular feat of any still-working composer. Throughout the past 50 years, he has composed scores for more than 200 films, including “The Ten Commandments,” “The Magnificent Seven,” “To Kill A Mockingbird,” “The Man With a Golden Arm, “Walk on the Wild Side,” “The Great Escape,” “Hud,” “Ghostbusters,” “My Left Foot,” “The Grifters,” “The Age of Innocence” and “Keeping the Faith.”

And he is still going strong. Seated in his composition studio in the lush hills at the base of the Santa Barbara mountains (complete with a baby grand piano, acoustic piano, speakers, VCR, metronome, mixers and music charts), he can, in one swivel move, observe his entire career. The original bound charts and recordings of his work are displayed neatly in a wall unit that also holds his numerous awards, including the Oscar® he won for “Thoroughly Modern Millie.” On the opposite wall, there is a photo gallery, a Who’s Who of Hollywood from its golden years to the present, digital era. “One thing the instruments of modern audio technology cannot reproduce accurately is strings,” he admonishes. “There is simply no sound like them.”

2001 was celebrated with many tributes and honors, as no film composer can come close to his lifetime achievements and musical accomplishments. He received the prestigious Founder’s Award, given by ASCAP (American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers). The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences also feted Bernstein, an evening hosted by good friend Carl Reiner and presented by various directors, actors and scholars. It was immediately followed by a month long film festival at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. This fall, the composer conducts at London’s Royal Albert Hall with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, and plans for a similar film festival are being developed.

Such honors have usually saluted retirement, but not for Bernstein. When not scoring a film, he is on the go, conducting orchestras in locales as diverse as Barcelona, Dallas and Warsaw, writing concertos, giving lectures, raising monies for music preservation non-profits and teaching both students and neophyte film composers.

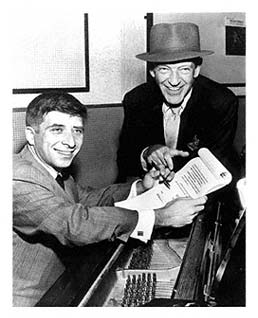

Elmer Bernstein with Cecil B. DeMille (1955).

Photo courtesy The Bernstein Family Trust

How does he account for his remarkable longevity? According to Bernstein, it is due in no small part to the superb musical training he received from one of his mentors, the renowned composer Aaron Copland, who took an early interest in his career. He subsequently studied with Roger Sessions and Stefan Wolpe. The musical template, as well as his unconditional love of virtually all music, aptly illustrates how the man who composed much of the ballet music in Jerome Robbins’ 1954 stage production of “Peter Pan,” as well as the ballet music for the film Oklahoma could, 30 years later, score the video of Michael Jackson’s “Thriller.” In short, he developed an incredible versatility.

“My approach to much of my composing film scores, is straightforward,” he explains. “I first review the time period, structure and plot of the film and ask one critical question, ‘Why is there music here?’ How does it move the emotional current in the story?’ In the case of ‘To Kill a Mockingbird,’ so many of the issues, including racism, murder, poverty, justice, poetic and otherwise—adult concepts to be sure—were viewed through the eyes of children. This profoundly influenced the theme and my recurring use of a simple piano and flute melody.”

With Fred Astaire (1963). Photo courtesy The Bernstein Family Trust

The son of Ukrainian immigrants, Bernstein, whose first language was Yiddish from his maternal grandmother, was born in Brooklyn and his boyhood days were spent in New York City. The family’s summer retreats were long vacations to Woodstock, where he still spends time while on the East Coast. He discovered his love of music growing up with a family interested in the arts and was encouraged by them in his various creative pursuits. He first studied with Henriette Michelson, won a four-year composition scholarship at Chatam Square School and attended NYU.

His first career in music was as a concert pianist. World War II provided him with the chance to arrange American folk music and to write dramatic scores for the Army Air Corps Radio Shows. In 1949, he was asked to do two shows for United Nations Radio, which brought him to the attention of Sidney Buchman, then a Vice President of Columbia Pictures. Mr. Buchman offered him the opportunity to write the music for “Saturday’s Hero” in 1950 and “Boots Malone” in 1951. He attracted more attention in 1952 with his unusual score for the motion picture “Sudden Fear,” featuring Joan Crawford and Jack Palance.

Bernstein suffered the fate of many of the great talents during the Fifties when his career with the studios was slowed by the McCarthy era. Having been sympathetic to then left-wing causes, he found himself “graylisted” in Hollywood. During this time, Bernstein was forced to work on two low-budget science fiction films, which became, and remain today, cult favorites, “Robot Monster” and “Cat Women of the Moon.” In spite of these small budget movies, or maybe because of it, he established himself a true innovator, pioneering early experiments in the use of electronic music.

He credits Cecil B. DeMille with bringing him back into the mainstream. “I was summoned to DeMille’s office and, knowing that he was not exactly a bastion of liberal causes, was most surprised at the two direct questions he asked me,” Bernstein recalls. ‘Are you a Communist?’ (I said ‘No’) and “Do you think you could do for ancient Egyptian music what Puccini did for Japanese music in ‘Madame Butterfly’?” (‘I don’t know, but I would like to try’) and that was the end of the conversation and apparently the end of my banishment!” Originally hired to write only the ancient dance music for “The Ten Commandments,” Bernstein eventually composed the entire score. Fellow film composer James Newton Howard (“The Sixth Sense,” “Wyatt Earp”) characterizes his first, indelible impression as a young boy after seeing the scene in which Moses first encounters God as the burning bush:

“The glorious ensemble of strings never sounding more heavenly, exquisitely restrained in their execution, yet resonating with a level of humanity that spoke at once of awesome power and gentleness-that spoke beyond any specific conflict to the human condition itself. It was the music which coalesced the disparate elements in the scene into a timeless moment of filmic storytelling.”

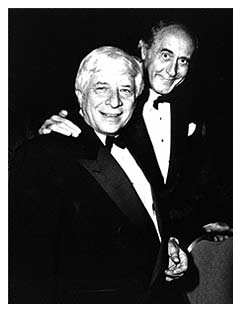

In the studio with Frank Sinatra (1958). Photo courtesy of The Bernstein Family Trust

During the yearlong process of scoring “The Ten Commandments,” Bernstein was hired by Otto Preminger to compose the score “The Man with the Golden Arm” after Preminger’s brother heard his score for the film noir “Sudden Fear.” Bernstein proposed a Hollywood first, an all-jazz score. Played by a big band assembled by Shorty Rogers, with Shelly Manne on the drums, the hot jazz sound perfectly externalized the emotions of Preminger’s tormented hero, a heroin-addicted jazz musician played by Frank Sinatra. The acclaimed score was nominated for an Academy award, the first of his 13 nominations.

“My colleagues told me that one film maketh not the man, but two really good, back-to-back scores for box office hits could produce a successful composer. And luckily, those were they.”

Bernstein’s music is also celebrated with many compositions for theatre (he had two Tony nominations for “How Now Dow Jones” and “Merlin”). Although erudite and interested in many areas of art, literature, politics and history, he has an equally developed sense of humor. His longtime association with the Ray and Charles Eames design team involved his scoring many of their “industrial” films. At one point, the couple was in a conundrum as to how to illustrate the variety of Westinghouse products to its investors at the annual shareholders’ meeting. Bernstein, recognizing that it might be a bit difficult to make can openers and vacuum cleaners appear interesting and profitable, opted to do a musically alphabetical list “using a patiche cantata, tongue firmly planted in cheek.” His classic “Toccata for Toy Trains,” one of the Eames’ notable documentary films, added another accolade to his long list of awards, the Downbeat, and a Grammy nomination. The film and score continue to be a favorite at festivals and museum retrospectives.

With Henry Mancini (1980).

But enough of the swivel view of his past career. He’s busy at work now, dividing time between his Santa Barbara and Santa Monica studios, adding the finishing touches to his composition for Martin Scorsese’s “Gangs of New York.” “Marty is one of the few directors who completely understands every aspect of filmmaking. We discuss the characters, the plot, and the nuances of every scene before a note is put to paper. It’s my sixth collaboration with him, so we have developed a ‘speak.'”

Does this man relax? It’s a relative word. The calendar is already beginning to fill up for the year—a working trip to London, an upcoming honor by the University of Judaism, a pending séjour at Cannes, an extended boating trip to the Alaskan waters with his family and friends are already works in progress. Then there are several evenings at the opera and time for lunches at his favorite haunt, the Polo Lounge. It’s a good life. And how does he see his place in musical history?

“One day last summer, I had finished a wonderful concert series in Barcelona and I was trying to locate an old acquaintance in the Catalonian countryside. It proved more difficult than I had imagined and I sat down at an alfresco café to recover from my failed mission over a cool drink, when I saw a small child filled with glee at the prospect of a ride on a mechanical horse. As the horse began its canter, strains of ‘The Magnificent Seven’ filled the air. It was an epiphany.”

Copyright 2002 Lifestyles Magazine